Qualified Mortgage Interest and Average Principal Amount

Introduction: The Law

The mortgage interest deduction allows taxpayers to deduct interest paid on qualified residence loans. Under the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA), the maximum loan amount eligible for deduction is $750,000 for mortgages incurred after December 15, 2017.

IRC 163(h)(3)(B)(ii) establishes the basis for calculating qualified mortgage interest:

The aggregate amount treated as acquisition indebtedness for any period shall not exceed $1,000,000 ($500,000 in the case of a married individual filing a separate return).

This limit was subsequently modified by IRC 163(h)(3)(F)(i):

Limitation on acquisition indebtedness. Subparagraph (B)(ii) shall be applied by substituting “$750,000 ($375,000” for “$1,000,000 ($500,000”.

This post provides a mathematically accurate method for computing qualified mortgage interest directly, as well as a refined approach to defining the average mortgage balance. Before introducing the new method, let’s review the nature of the problem.

The Nature of the Problem

From a purely mathematical perspective, independent of tax law, the interest amount for loan \(i\) is the integral of the interest per dollar per day (\(\alpha_i\)) multiplied by the loan amount (\(L_i\)) over time. The total interest paid across all loans can be expressed as:

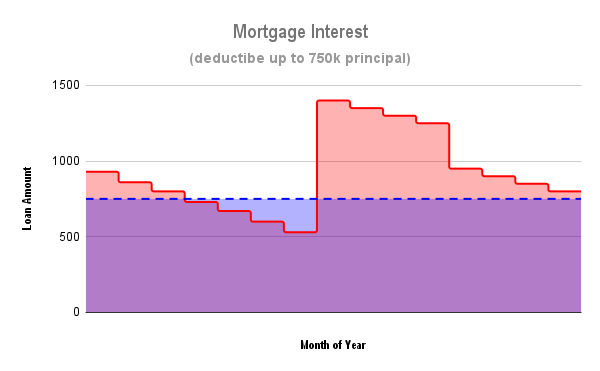

\[\text{Total Interest} = \sum_{i=1}^{n} \int_0^{T} \alpha_i \times L_i(t) \, dt \tag{1}\]Apart from the factor of \(\alpha_i\), the total interest corresponds to the total area under the curve (the light purple and dark purple areas combined) shown in the diagram.

The law simply imposes a restriction on the loan amounts eligible for deduction:

\[\sum_{i=1}^{n} L_i(t) \leq 750,000 \tag{2}\]Thus, the qualified interest corresponds only to the dark purple area.

Note that the law restricts only the total loan amount eligible for the deduction; it does not dictate exactly which loans must be included. Therefore, we have flexibility: we can allocate proportionally across loans or allocate optimally by prioritizing loans with the higher interest rate \(\alpha\).

IRS-Provided Methods

The IRS cannot expect every taxpayer to know calculus and carry out the integral. Instead, they provide an average balance method to prorate the interest generated by a $750,000 loan amount as:

\[\text{Qualified Interest} = \text{Total Interest} \times \min\left(1, \frac{750,000}{\text{Average Balance}}\right) \tag{3}\]Under Treasury Regulation §1.163-10T(h), several acceptable methods are available for determining the average balance of debt secured by a qualified residence:

-

Daily Basis Method (Reg. §1.163-10T(h)(3)):

This method calculates the average mortgage balance by weighting the actual principal outstanding each day over the course of the year. This can favor taxpayers by averaging down the balance when you do not have a loan during some months but still own the home as a residence. For example, John Smith starts 2024 with a $1.5 million mortgage and pays it off on June 30. Under this method, his average balance is about $750,000, allowing full deduction of the interest paid.

-

Interest Rate Method (Reg. §1.163-10T(h)(4)):

This method calculates the average balance based on the ratio between the interest paid and the stated interest rate of the debt.

-

Beginning and Ending Balance Method (Reg. §1.163-10T(h)(5)):

This approach allows the taxpayer to determine the average balance by taking the simple average of the beginning and ending loan balances for the year. However, this method may only be used when no new borrowing occurred during the tax year.

-

Highest Balance Method (Reg. §1.163-10T(h)(6)):

Alternatively, the average balance can be approximated by taking the highest principal balance outstanding at any time during the year.

This method is generally the most disadvantageous for taxpayers because it often lowers the deductible mortgage interest by locking in the highest debt level, even if the balance dropped later.

For this reason, I specifically ask for the year-end mortgage balance in my checklist, so that I can apply a more favorable calculation method—which may lower the average balance and thus maximize the mortgage interest deduction.

Furthermore, Reg. §1.163-10T(h)(8) establishes an anti-abuse provision. Under this rule, if the IRS determines that a taxpayer’s chosen method materially overstates the interest deduction, the IRS has the authority to adjust the calculation using a more appropriate method to correctly reflect the average balance of the debt.

Our Proposed Direct Method

While the IRS-supplied methods work well in some simple cases, they cannot be applied in more complicated situations, or doing so will produce unreasonable results. Let us use an examples to illustrate the problem.

Alice had a $750,000 mortgage loan and paid $40,000 in interest. She pays interest only, so the principal balance remains $750,000 throughout the year; this is her average balance. According to equation (3), the full amount of $40,000 is deductible.

Bob had the same loan as Alice, but additionally he had another $750,000 interest-only mortgage loan and paid $30,000 in interest. Bob had a constant and average balance of $1,500,000, and according to formula (3), his deductible mortgage interest is $35,000, which is lower than Alice’s even though he had one more loan. This is not reasonable.

Our proposal is to simply carry out the integral directly. For each loan, as we only have the principal balances at the beginning and at the end of the loan duration, and the total amount of interest paid for the duration, we have to assume the principal is a linear function over time.

Where there are two or more loans at the same time, we perform the integral over different sections of the time period where the principal balance is continuous and then add the results together, i.e.:

\[\text{Total Interest} = \sum_{i=1}^{n} \int_0^{T1} \alpha_i \times L_i(t) \, dt + \sum_{i=1}^{n} \int_{T1}^{T2} \alpha_i \times L_i(t) \, dt + ... \tag{4}\]During each period, we allocate as much amount as allowed by Equation (2) to the loan with the higher interest rate \(\alpha\) to produce the maximum total interest.

The method I describe is similar to the “Simplified Method” or “Exact Method” outlined in Treasury Regulation §1.163-10T(d) and §1.163-10T(e) for situations where the secured debt exceeds the adjusted purchase price. Although not explicitly listed among the IRS’s provided methods, this calculation approach is fully defensible because it is based on statutory law and sound mathematical principles.

Using the direct method, Bob would have a qualified interest of $40,000.

Average Loan Balance Defined

Since we have already calculated the yearly qualified mortgage interest directly, we no longer need to compute the yearly average mortgage balance to derive it.

However, we can define the average mortgage balance as the hypothetical loan amount that, if kept constant throughout the year, would generate the same qualified interest we calculated.

In other words, it’s the balance that would make equation (3) hold. Solving for the average mortgage balance:

\[\text{Average Mortgage Balance} = 750,000 \times \frac{\text{Total Interest Paid}}{\text{Qualified Interest}} \tag{5}\]You might wonder why we still need to calculate the average mortgage balance if the qualified interest is already known. There are two important reasons:

- First, the IRS requires the reporting of average mortgage balances in Table 1 of Publication 936 to calculate qualified mortgage interest using the total interest paid and the average balance.

- Second, we must provide the total interest information for state tax returns. While federal tax law caps the deductible amount at $750,000, some states apply different limits—or no limits at all—allowing full mortgage interest deductions without federal restrictions.

Thus, by calculating the average principal, we retain flexibility to apply either the $750,000 federal limit or more generous state-specific rules as needed.

Implementation

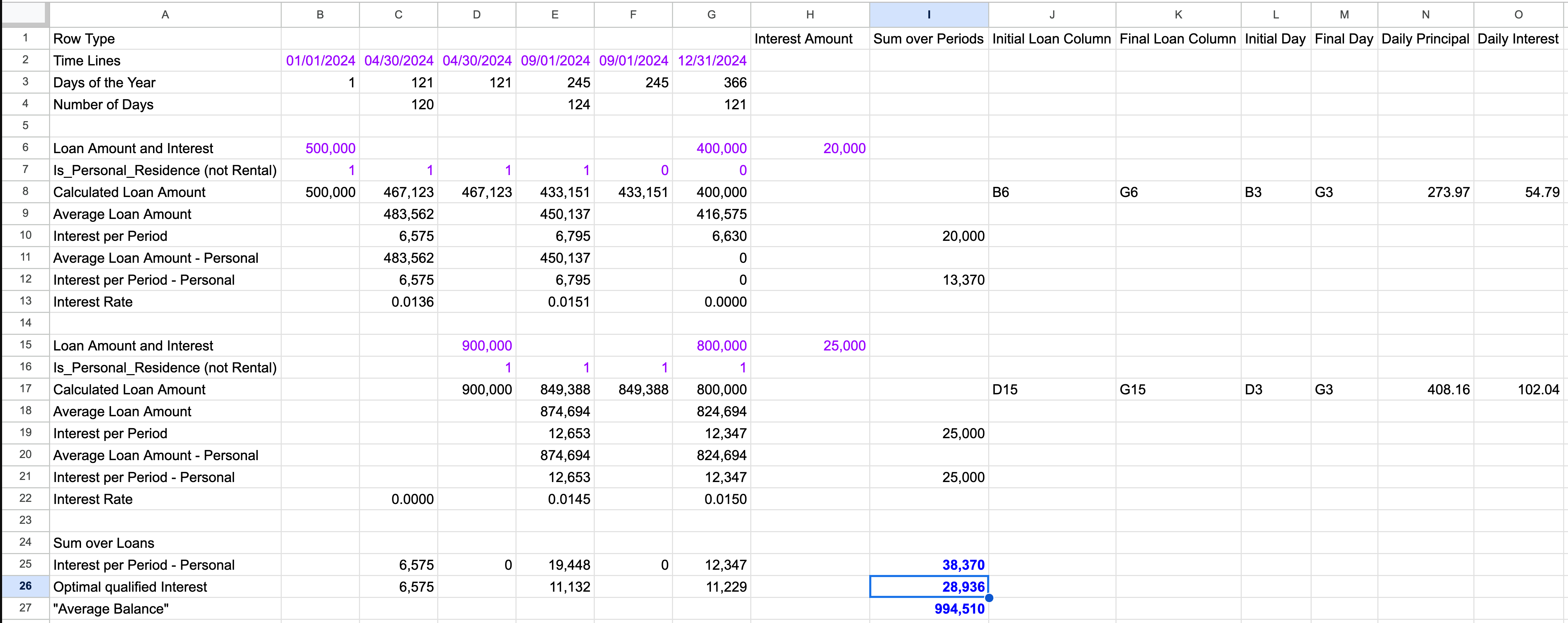

Since spreadsheets are surprisingly powerful (and even Turing complete), we developed a Google Sheets tool to automate the entire process.

- You enter the inputs (highlighted in purple) such as loan dates, balances, and use type.

- The qualified interest results (highlighted in blue) are calculated automatically.

- A sample spreadsheet screenshot demonstrates the structure and formulas used.