How to withhold taxes for RSU's

RSU (Restricted Stock Unit) refers to stocks of the company itself issued to reward employees. Taxation on RSUs is divided into two steps: pay tax on the value of the RSUs when they are received, and pay tax on the appreciation when the RSUs are sold.

For example, the company thinks that John has great potential and promises to give him RSUs. A year later, John performs well, and the company fulfills its promise by giving him (exercising) some of the RSUs. The reason for giving only a portion of the RSUs is that the company is afraid John will change jobs after receiving them. Suppose John gets 100 shares, each worth $1,000 when received, so he has $100,000 in non-cash income. Although not cash, it is real wealth, and can be easily converted to cash, and so John needs to pay tax on it. The company automatically adds this income to W-2 box 1 without John’s consent, and John pays tax on it along with his salary when filing taxes.

A year later, John wants to buy a house and needs to sell stocks to pay the down payment. At this time, each share is worth $1,200. Since John has already paid tax on the original $1,000 per share, he only needs to pay tax on the $200 appreciation per share. This is equivalent to John buying the company’s stock at $1,000 per share initially. In addition, there is no difference in capital gains tax between this and other ordinary stocks. Many people mistakenly think that since they didn’t spend money to buy the stocks, they need to pay tax on the entire $1,200 income. In reality, this is unnecessary, as the tax office will not thank you for paying tax twice on the $1,000 income, and there are other ways to express patriotism.

Some people do not understand why they were promised 100 shares but only received 70 shares, and yet still have to pay tax on the 30 shares they didn’t get. To address this confusion, consider the situation in two steps: First, the company gives you all 100 shares, and you pay tax on them at $1,000 per share. Then, the company sells 30 shares (sell to cover) on the same day they are received, resulting in no capital gains. The proceeds from the stock sale are reflected in W-2 box 2 (tax withheld) and are equivalent to being returned to your pocket. This scenario is similar to having a salary of $200,000 but only receiving a little over $100,000, while still having to pay tax on the full $200,000 amount in W-2 box 1.

f you have deep pockets, you can certainly pay the withholding tax in cash. However, most people are not aware of this option, and even if they are, there is always a psychological barrier to taking out cash. As a result, the company uses stocks to pay your taxes. Of course, the IRS does not accept stocks, so the stocks are still converted into dollars and given to the IRS.

There are two ways to pay taxes with stocks:

- Suppose John works at:

- Google,

- Facebook, or

- Microsoft,

the company directly deducts a portion of the shares, for example, 30 shares, and only deposits 70 shares into John’s account. John never sees the 30 shares and does not need to report it.

- On the other hand, if John works at:

- Amazon,

- Uber, or

- Zillow,

the company deposits 100 shares in John’s account and then immediately sells a portion of them to pay taxes. In this case, John will receive a 1099-B and needs to report the stock transactions, even though the capital gains are zero or close to zero. If you don’t report, the IRS will send you a letter asking for the tax on the proceeds, as they do not know, or pretend that they do not know that you have paid taxes on the proceeds already on W-2.

To determine which method your company uses, simply check with the stock company to see if there is a 1099; if there is one, report it, and if there isn’t, don’t.

All of this is handled by the company, and John is very busy, assuming that as long as the taxes have been paid, there should be no problem. However, when it comes to filing taxes, he encounters a surprise. This is not a binary issue of paying or not paying taxes, as a programmer might be familiar with, but rather a quantitative matter of how much taxes being paid. The default choice is to pay a 22% federal tax (apart from state taxes and FICA taxes), but as an experienced programmer, John’s highest tax rate is 32%. As a result, John owes an additional 10% or $10,000 in taxes on the RSU. Generally, penalties are incurred for underpayment of taxes. If the stock price goes up, it’s easier to handle, but if it goes down, it would have been better to sell more shares to pay taxes at the time. Even if the stock price goes up, John still has unsold shares, so paying the full amount of taxes would be a good strategy of hedging.

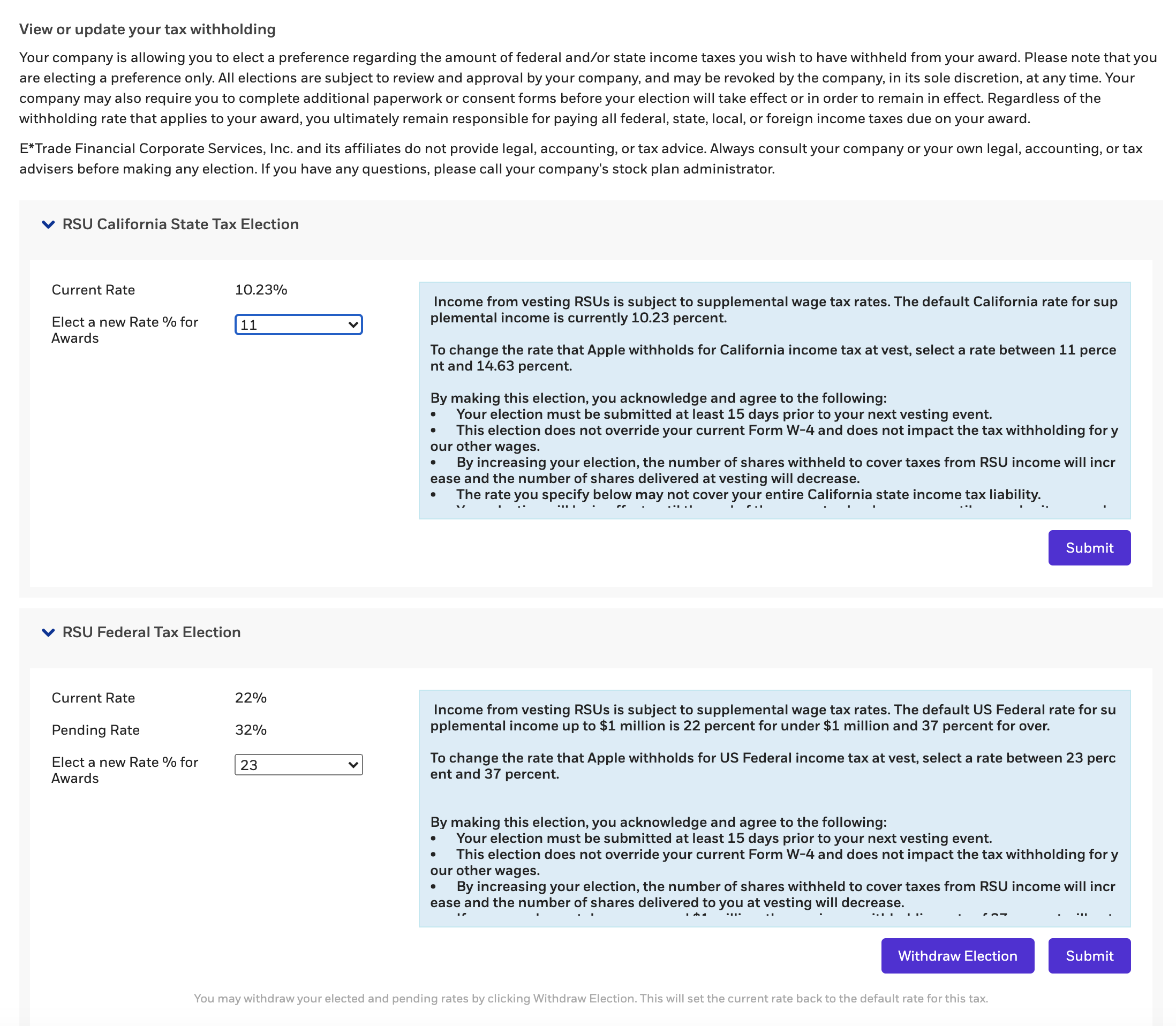

The method to pay the full amount is simple: adjust the tax rate on the RSUs to your highest tax rate (marginal rate), as shown in the figure.

Apple and Google both offer this option. If your company does not provide this choice, you may consider changing companies or manually handling it by selling stocks and paying a little more tax each time you receive a salary. The specific steps can be found in this post. The highest tax rate data can be found on the second page of the tax documents I provided for John, he can also refer to this tax rate table.

I hope I have explained the main points clearly. As the saying goes, the devil is in the details. If you want to learn more about RSUs, ISOs, and ESPPs, please read this post of mine.